New volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica > Volume 30, K-MOR

(187) Page 163

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

UNITED STATES]

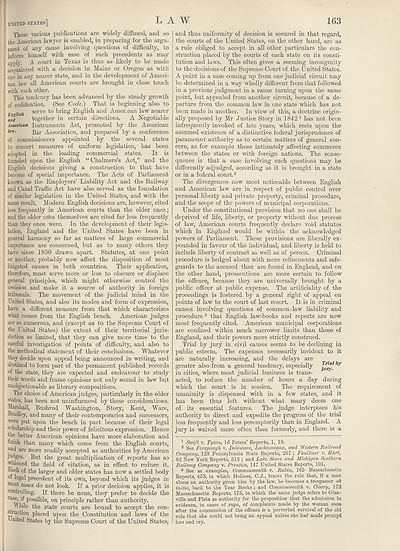

These various publications are widely diffused, and so

the American lawyer is enabled, in preparing for the argu¬

ment of any cause involving questions of difficulty, to

inform himself with ease of such precedents as may

apply. A court in Texas is thus as likely to be made

acquainted with a decision in Maine or Oregon as with

one in any nearer state, and in the development of Ameri¬

can law all American courts are brought in close touch

with each other.

This tendency has been advanced by the steady growth

of codification. (See Code.) That is beginning also to

Ea list serve f° bring English and American law nearer

and together in certain directions. A Negotiable

American Instruments Act, promoted by the American

law- Bar Association, and prepared by a conference

of commissioners appointed by the several states

to concert measures of uniform legislation, has been

adopted in the leading commercial states. It is

founded upon the English “ Chalmers’s Act,” and the

English decisions giving a construction to that have

become of special importance. The Acts of Parliament

known as the Employers’ Liability Act and the Railway

and Canal Traffic Act have also served as the foundation

of similar legislation in the United States, and with the

same result. Modern English decisions are, however, cited

less frequently in American courts than the older ones;

and the older ones themselves are cited far less frequently

than they once were. In the development of their legis¬

lation, England and the United States have been in

general harmony so far as matters of large commercial

importance are concerned, but as to many others they

have since 1850 drawn apart. Statutes, at one point

or another, probably now affect the disposition of most

litigated causes in both countries. Their application,

therefore, must serve more or less to obscure or displace

general principles, which might otherwise control the

decision and make it a source of authority in foreign

tribunals. The movement of the judicial mind in the

United States, and also its modes and form of expression,

have a different measure from that which characterizes

what comes from the English bench. American judges

are so numerous, and (except as to the Supreme Court of

the United States) the extent of their territorial juris¬

diction so limited, that they can give more time to the

careful investigation of points of difficulty, and also to

the methodical statement of their conclusions. Whatever

they decide upon appeal being announced in writing, and

destined to form part of the permanent published records

of the state, they are expected and endeavour to study

their words and frame opinions not only sound in law but

unobjectionable as literary compositions.

The choice of American judges, particularly in the older

states, has been not uninfluenced by these considerations.

Marshall, Bushrod Washington, Story, Kent, Ware,

Bradley, and many of their contemporaries and successors,

were put upon the bench in part because of their legal

scholarship and their power of felicitous expression. Hence

the better American opinions have more elaboration and

finish than many which come from the English courts,

and are more readily accepted as authorities by American

judges. But the great multiplication of reports has so

widened the field of citation, as in effect to reduce it.

Each of the larger and older states has now a settled body

of legal precedent of its own, beyond which its judges in

most cases do not look. If a prior decision applies, it is

controlling. If there be none, they prefer to decide the

case,^ if possible, on principle rather than authority.

While the state courts are bound to accept the con¬

struction placed upon the Constitution and laws of the

United States by the Supreme Court of the United States,

163

and thus uniformity of decision is secured in that regard,

the courts of the United States, on the other hand, are as

a rule obliged to accept in all other particulars the con¬

struction placed by the courts of each state on its consti¬

tution and laws. This often gives a seeming incongruity

to the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States.

A point in a case coming up from one judicial circuit may

be determined in a way wholly different from that followed

in a previous judgment in a cause turning upon the same

point, but appealed from another circuit, because of a de¬

parture from the common law in one state which has not

been made in another. In view of this, a doctrine origin¬

ally proposed by Mr Justice Story in 1842 1 has not been

infrequently invoked of late years, which rests upon the

assumed existence of a distinctive federal jurisprudence of

paramount authority as to certain matters of general con¬

cern, as for example those intimately affecting commerce

between the states or with foreign nations. The conse¬

quence is that a case involving such questions may be

differently adjudged, according as it is brought in a state

or in a federal court.2

The divergences now most noticeable between English

and American law are in respect of public control over

personal liberty and private property, criminal procedure,

and the scope of the powers of municipal corporations.

Under the constitutional provision that no one shall be

deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process

of law, American courts frequently declare void statutes

which in England would be within the acknowledged

powers of Parliament. These provisions are liberally ex¬

pounded in favour of. the individual, and liberty is held to

include liberty of contract as well as of person. Criminal

procedure is hedged about with more refinements and safe¬

guards to the accused than are found in England, and on

the other hand, prosecutions are more certain to follow

the offence, because they are universally brought by a

public officer at public expense. The artificiality of the

proceedings is fostered by a general right of appeal on

points of law to the court of last resort. It is in criminal

causes involving questions of common-law liability and

procedure 3 that English law-books and reports are now

most frequently cited. American municipal corporations

are confined within much narrower limits than those of

England, and their powers more strictly construed.

Trial by jury in civil causes seems to be declining in

public esteem. The expenses necessarily incident to it

are naturally increasing, and the delays are

greater also from a general tendency, especially Jury1 by

in cities, where most judicial business is trans¬

acted, to reduce the number of hours a day during

which the court is in session. The requirement of

unanimity is dispensed with in a few states, and it

has been thus left without what many deem one

of its essential features. The judge interposes his

authority to direct and expedite the progress of the trial

less frequently and less peremptorily than in England. A

jury is waived more often than formerly, and there is a

1 Swift v. Tyson, 16 Peters’ Reports, 1, 19.

2 See Forepauyh v. Delaware, Lackaioanna, and Western Railroad

Company, 128 Pennsylvania State Reports, 267 ; Faulkner v. Hart,

82 New York Reports, 313 ; and Lake Shore and Michigan Southern

Railway Company v. Prentice, 147 United States Reports, 101.

3 See as examples, Commonwealth v. Rubin, 165 Massachusetts

Reports, 453, in which Holmes, C.J., traces the rule that, if a man

abuse an authority given him by the law, he becomes a trespasser ab

initio, back to the Year Books ; and Commonwealth v. Cleary, 172

Massachusetts Reports, 175, in which the same judge refers to Glan-

ville and Fleta as authority for the proposition that the admission in

evidence, in cases of rape, of complaints made by the woman soon

after the commission of the offence is a perverted survival of the old

rule that she could not bring an appeal unless she had made prompt

hue and cry.

LAW

These various publications are widely diffused, and so

the American lawyer is enabled, in preparing for the argu¬

ment of any cause involving questions of difficulty, to

inform himself with ease of such precedents as may

apply. A court in Texas is thus as likely to be made

acquainted with a decision in Maine or Oregon as with

one in any nearer state, and in the development of Ameri¬

can law all American courts are brought in close touch

with each other.

This tendency has been advanced by the steady growth

of codification. (See Code.) That is beginning also to

Ea list serve f° bring English and American law nearer

and together in certain directions. A Negotiable

American Instruments Act, promoted by the American

law- Bar Association, and prepared by a conference

of commissioners appointed by the several states

to concert measures of uniform legislation, has been

adopted in the leading commercial states. It is

founded upon the English “ Chalmers’s Act,” and the

English decisions giving a construction to that have

become of special importance. The Acts of Parliament

known as the Employers’ Liability Act and the Railway

and Canal Traffic Act have also served as the foundation

of similar legislation in the United States, and with the

same result. Modern English decisions are, however, cited

less frequently in American courts than the older ones;

and the older ones themselves are cited far less frequently

than they once were. In the development of their legis¬

lation, England and the United States have been in

general harmony so far as matters of large commercial

importance are concerned, but as to many others they

have since 1850 drawn apart. Statutes, at one point

or another, probably now affect the disposition of most

litigated causes in both countries. Their application,

therefore, must serve more or less to obscure or displace

general principles, which might otherwise control the

decision and make it a source of authority in foreign

tribunals. The movement of the judicial mind in the

United States, and also its modes and form of expression,

have a different measure from that which characterizes

what comes from the English bench. American judges

are so numerous, and (except as to the Supreme Court of

the United States) the extent of their territorial juris¬

diction so limited, that they can give more time to the

careful investigation of points of difficulty, and also to

the methodical statement of their conclusions. Whatever

they decide upon appeal being announced in writing, and

destined to form part of the permanent published records

of the state, they are expected and endeavour to study

their words and frame opinions not only sound in law but

unobjectionable as literary compositions.

The choice of American judges, particularly in the older

states, has been not uninfluenced by these considerations.

Marshall, Bushrod Washington, Story, Kent, Ware,

Bradley, and many of their contemporaries and successors,

were put upon the bench in part because of their legal

scholarship and their power of felicitous expression. Hence

the better American opinions have more elaboration and

finish than many which come from the English courts,

and are more readily accepted as authorities by American

judges. But the great multiplication of reports has so

widened the field of citation, as in effect to reduce it.

Each of the larger and older states has now a settled body

of legal precedent of its own, beyond which its judges in

most cases do not look. If a prior decision applies, it is

controlling. If there be none, they prefer to decide the

case,^ if possible, on principle rather than authority.

While the state courts are bound to accept the con¬

struction placed upon the Constitution and laws of the

United States by the Supreme Court of the United States,

163

and thus uniformity of decision is secured in that regard,

the courts of the United States, on the other hand, are as

a rule obliged to accept in all other particulars the con¬

struction placed by the courts of each state on its consti¬

tution and laws. This often gives a seeming incongruity

to the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States.

A point in a case coming up from one judicial circuit may

be determined in a way wholly different from that followed

in a previous judgment in a cause turning upon the same

point, but appealed from another circuit, because of a de¬

parture from the common law in one state which has not

been made in another. In view of this, a doctrine origin¬

ally proposed by Mr Justice Story in 1842 1 has not been

infrequently invoked of late years, which rests upon the

assumed existence of a distinctive federal jurisprudence of

paramount authority as to certain matters of general con¬

cern, as for example those intimately affecting commerce

between the states or with foreign nations. The conse¬

quence is that a case involving such questions may be

differently adjudged, according as it is brought in a state

or in a federal court.2

The divergences now most noticeable between English

and American law are in respect of public control over

personal liberty and private property, criminal procedure,

and the scope of the powers of municipal corporations.

Under the constitutional provision that no one shall be

deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process

of law, American courts frequently declare void statutes

which in England would be within the acknowledged

powers of Parliament. These provisions are liberally ex¬

pounded in favour of. the individual, and liberty is held to

include liberty of contract as well as of person. Criminal

procedure is hedged about with more refinements and safe¬

guards to the accused than are found in England, and on

the other hand, prosecutions are more certain to follow

the offence, because they are universally brought by a

public officer at public expense. The artificiality of the

proceedings is fostered by a general right of appeal on

points of law to the court of last resort. It is in criminal

causes involving questions of common-law liability and

procedure 3 that English law-books and reports are now

most frequently cited. American municipal corporations

are confined within much narrower limits than those of

England, and their powers more strictly construed.

Trial by jury in civil causes seems to be declining in

public esteem. The expenses necessarily incident to it

are naturally increasing, and the delays are

greater also from a general tendency, especially Jury1 by

in cities, where most judicial business is trans¬

acted, to reduce the number of hours a day during

which the court is in session. The requirement of

unanimity is dispensed with in a few states, and it

has been thus left without what many deem one

of its essential features. The judge interposes his

authority to direct and expedite the progress of the trial

less frequently and less peremptorily than in England. A

jury is waived more often than formerly, and there is a

1 Swift v. Tyson, 16 Peters’ Reports, 1, 19.

2 See Forepauyh v. Delaware, Lackaioanna, and Western Railroad

Company, 128 Pennsylvania State Reports, 267 ; Faulkner v. Hart,

82 New York Reports, 313 ; and Lake Shore and Michigan Southern

Railway Company v. Prentice, 147 United States Reports, 101.

3 See as examples, Commonwealth v. Rubin, 165 Massachusetts

Reports, 453, in which Holmes, C.J., traces the rule that, if a man

abuse an authority given him by the law, he becomes a trespasser ab

initio, back to the Year Books ; and Commonwealth v. Cleary, 172

Massachusetts Reports, 175, in which the same judge refers to Glan-

ville and Fleta as authority for the proposition that the admission in

evidence, in cases of rape, of complaints made by the woman soon

after the commission of the offence is a perverted survival of the old

rule that she could not bring an appeal unless she had made prompt

hue and cry.

LAW

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > New volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica > Volume 30, K-MOR > (187) Page 163 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193569932 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.18 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|