Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 8, DIA-England

(549) Page 539

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

EGYPT.

i/pt. its appearance presents a character altogether new ; and

if itS general plan suggests the idea of a private habita¬

tion, and seems to exclude that of a temple, the magnifi¬

cence of the decoration, the profusion of the sculptures,

the beauty of the materials, and the perfection of the

execution, prove that this habitation formerly belonged

to a rich and powerful sovereign. The remains of this

palace occupy only the extremity of an artificial mound

or bank of earth, on which there were formerly other

structures connected with that which still exists ; at least

all the fragments scattered over the ground bear royal

names belonging either to the last Pharaohs of the eigh¬

teenth or the first of the nineteenth dynasty. In the same

line with these remains rises a portico a hundred and fifty

feet in length and thirty in height, supported by ten

columns, whose shafts are composed of wreaths of lotus-

stems, whilst the capitals are formed of buds and flowers

of the same plant, truncated so as to admit the coping.

On the four faces of the capitals are sculptured with much

care the royal legends of Menephtha I. and also those of

Rhamses the Great; and the names of these Pharaohs

are likewise inscribed on the shafts of the columns, but

joined together and included in a square tablet. The de¬

dicatory legend which adorns the architrave of the por¬

tico, occupying its whole length, establishes two principal

facts; first, that the palace of Kournah was founded and

erected by Menephtha I.; and, secondly, that his son

Rhamses the Great, having completed the decoration of

the edifice, surrounded it with an enceinte ornamented

with propylons, and similar to that within which each of

the greatroyal monuments at Thebes is contained. In fact,

all the bas-reliefs which decorate the interior of the por¬

tico, and the exterior of the three gates which lead to the

apartments of the Menephtheion, represent Menephtha I.

and more frequently still Rhamses the Great, rendering

homage to the Theban triad and to the other divinities of

Egypt, or receiving from the munificence of the gods royal

powers and precious gifts in order to embellish and prolong

life. And the only sculptures of the edifice posterior to

the time of Rhamses the Great consist of some royal

onomastic inscriptions, placed either on the sides or base¬

ment of the gates, but wholly unconnected with the pri¬

mitive decoration ; all of them, with the exception of one

which contains the names and titles of Rhamses-Meia-

moun, belonging to the reign of Menephtha II. the son

and immediate successor of Rhamses the Great.1

The catacombs in the western mountains are not less

abundant than the monuments we have described, in trea-

539

sures illustrative of the ancient history of Egypt. In the Egypt-

valley of Biban-el-Moiouk, a rocky ravine to the south-

west of Kournah, are the sepulchres of the kings of the

three Diospohtan or Theban dynasties, being the eigh¬

teenth, nineteenth, and twentieth.2 The site chosen for

the royal necropolis appears to be eminently suited to its

melancholy destination ; for a valley or ravine, encased, as

it were, by high precipitous rocks, or by mountains in a

state of decomposition, presenting large fissures, occa¬

sioned either by the extreme heat or by internal sinking

down, and the backs of which are covered with black

bands or patches, as if they had been in part burned, is a

spot which, from its loneliness, desolation, and apparent

decay, harmonizes well with otir ideas as to the most fit¬

ting locality for a place of tombs. No living animal, it is

said, frequents this valley of the dead; even the fox, the

wolf, and the hyena shun its mournful precincts; and its

doleful echoes are only awakened at intervals by the foot

of the solitary antiquary, led by inquisitive curiosity to

pry into the very secrets of the grave. The catacombs or

hypogcea are all constructed on nearly the same plan, yet

no two of them are exactly alike: some are complete,

others appear never to have been finished, and they vary

much in the depth to which they have been excavated.

In general, the entrance is by the exterior opening of a

passage twenty feet wide, which descends gradually about

fifty paces, then expands whilst the descent becomes more

rapid, and is continued for some distance farther. On

either side of this passage is a horizontal gallery, on a level

with the lowest part of the first descent; small chambers

also branch off sides of the second descent; at the inte¬

rior extremity there is a spacious and lofty apartment, in

the centre of which is placed the royal tomb ; and beyond

this there are commonly other small chambers at the sides,

whilst in some cases the principal passage is continued a

long way into the rock. The royal tomb is for the most

part a sarcophagus of red or grey granite, circular at the

one end and square at the other; but where there is no

sarcophagus a hole or grave is discovered, cut in the rock

to the depth of from six to thirty feet, and which ap¬

pears to have been covered by a granite lid. Almost all

the lids, however, belonging to the graves excavated in

the rock, have either been removed or broken. In those

sepulchres which have been finished, the walls from one

end to the other are all covered with sculptures and paint¬

ings executed in the best style of ancient art; and, owing

to the unparalleled dryness of the atmosphere in Egypt,

the colours, where they have not been purposely damaged.

1 Champollion, Lettres, 380, et seqq. It mav perhaps conduce to perspicuity, or at least serve to prevent mistakes, if we introduce

here the eight reigns anterior to that of Ithamses-Meiamoun, in their chronological order. They stand thus : 1. Amenophis II. or

Memnon ; 2. Horus ; 3. Rhamses I.; 4. Menephtha 1. or Ousirei; 5. llhamses the Great, or Sesostris ; 6. Menephtha II.; 7. Me¬

nephtha III.; 8. Rhamerreh ; and, 9- Ithamses-Meiamoun. The monuments of different orders having clearly demonstrated that

Rhamses the Great, the Sesostris of Herodotus, must be included in the eighteenth dynasty, as answering exactly to the Rhamses

called Mgyptus in the extracts of Manetho, it follows that in Rhamses-Meiamoun, the Rhamses-Sethos of the same lists of Manetho,

we recognise the head or chief of the nineteenth dynasty.

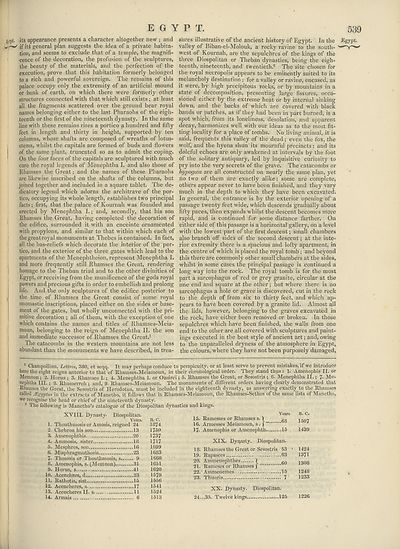

1 The following is Manetho’s catalogue of the Hiospolitan dynasties and kings.

XVIII. Dynasty- Diospolitan.

Years. B. C.

1. Thouthmosis or Amosis, reigned 24 1874

2. Chebron his son 13 1750

3. Amenophthis 20 1737

4. Ammosis, sister 18 1717

5. Mesphres, son 16 1699

6. Misphragmuthosis 23 1683

7- Thmosis or Thouthmosis, s 9 1660

8. Amenophis, s. (Memnon) 31 1651

9. Horus, s 41 1620

10. Acenchres, d 23 1579

11. Rathotis, sist 15 1556

12. Acencheres, s 17 1541

13. Acencheres II. s 11 1524

14. Armais 6 1513

Years.

15. Ramesses or Rhamses s. \ nj!

16. Armesses Meiamoun, s . f

17- Amenophis or Amenophth 15

B. C.

1507

1439

XIX. Dynasty. Diospolitan.

18. Rhamses the Great or Sesostris 53 ■

19. Rapasces 63

20. Ammenophthes \ #;n

21. Rameses or llhamses J

22. ' Ammenemes 15

23. Thuoris 7

XX. Dynasty. Diospolitan.

24...35. Twelve kings 125

1424

1371

1308

1248

1233

1226

i/pt. its appearance presents a character altogether new ; and

if itS general plan suggests the idea of a private habita¬

tion, and seems to exclude that of a temple, the magnifi¬

cence of the decoration, the profusion of the sculptures,

the beauty of the materials, and the perfection of the

execution, prove that this habitation formerly belonged

to a rich and powerful sovereign. The remains of this

palace occupy only the extremity of an artificial mound

or bank of earth, on which there were formerly other

structures connected with that which still exists ; at least

all the fragments scattered over the ground bear royal

names belonging either to the last Pharaohs of the eigh¬

teenth or the first of the nineteenth dynasty. In the same

line with these remains rises a portico a hundred and fifty

feet in length and thirty in height, supported by ten

columns, whose shafts are composed of wreaths of lotus-

stems, whilst the capitals are formed of buds and flowers

of the same plant, truncated so as to admit the coping.

On the four faces of the capitals are sculptured with much

care the royal legends of Menephtha I. and also those of

Rhamses the Great; and the names of these Pharaohs

are likewise inscribed on the shafts of the columns, but

joined together and included in a square tablet. The de¬

dicatory legend which adorns the architrave of the por¬

tico, occupying its whole length, establishes two principal

facts; first, that the palace of Kournah was founded and

erected by Menephtha I.; and, secondly, that his son

Rhamses the Great, having completed the decoration of

the edifice, surrounded it with an enceinte ornamented

with propylons, and similar to that within which each of

the greatroyal monuments at Thebes is contained. In fact,

all the bas-reliefs which decorate the interior of the por¬

tico, and the exterior of the three gates which lead to the

apartments of the Menephtheion, represent Menephtha I.

and more frequently still Rhamses the Great, rendering

homage to the Theban triad and to the other divinities of

Egypt, or receiving from the munificence of the gods royal

powers and precious gifts in order to embellish and prolong

life. And the only sculptures of the edifice posterior to

the time of Rhamses the Great consist of some royal

onomastic inscriptions, placed either on the sides or base¬

ment of the gates, but wholly unconnected with the pri¬

mitive decoration ; all of them, with the exception of one

which contains the names and titles of Rhamses-Meia-

moun, belonging to the reign of Menephtha II. the son

and immediate successor of Rhamses the Great.1

The catacombs in the western mountains are not less

abundant than the monuments we have described, in trea-

539

sures illustrative of the ancient history of Egypt. In the Egypt-

valley of Biban-el-Moiouk, a rocky ravine to the south-

west of Kournah, are the sepulchres of the kings of the

three Diospohtan or Theban dynasties, being the eigh¬

teenth, nineteenth, and twentieth.2 The site chosen for

the royal necropolis appears to be eminently suited to its

melancholy destination ; for a valley or ravine, encased, as

it were, by high precipitous rocks, or by mountains in a

state of decomposition, presenting large fissures, occa¬

sioned either by the extreme heat or by internal sinking

down, and the backs of which are covered with black

bands or patches, as if they had been in part burned, is a

spot which, from its loneliness, desolation, and apparent

decay, harmonizes well with otir ideas as to the most fit¬

ting locality for a place of tombs. No living animal, it is

said, frequents this valley of the dead; even the fox, the

wolf, and the hyena shun its mournful precincts; and its

doleful echoes are only awakened at intervals by the foot

of the solitary antiquary, led by inquisitive curiosity to

pry into the very secrets of the grave. The catacombs or

hypogcea are all constructed on nearly the same plan, yet

no two of them are exactly alike: some are complete,

others appear never to have been finished, and they vary

much in the depth to which they have been excavated.

In general, the entrance is by the exterior opening of a

passage twenty feet wide, which descends gradually about

fifty paces, then expands whilst the descent becomes more

rapid, and is continued for some distance farther. On

either side of this passage is a horizontal gallery, on a level

with the lowest part of the first descent; small chambers

also branch off sides of the second descent; at the inte¬

rior extremity there is a spacious and lofty apartment, in

the centre of which is placed the royal tomb ; and beyond

this there are commonly other small chambers at the sides,

whilst in some cases the principal passage is continued a

long way into the rock. The royal tomb is for the most

part a sarcophagus of red or grey granite, circular at the

one end and square at the other; but where there is no

sarcophagus a hole or grave is discovered, cut in the rock

to the depth of from six to thirty feet, and which ap¬

pears to have been covered by a granite lid. Almost all

the lids, however, belonging to the graves excavated in

the rock, have either been removed or broken. In those

sepulchres which have been finished, the walls from one

end to the other are all covered with sculptures and paint¬

ings executed in the best style of ancient art; and, owing

to the unparalleled dryness of the atmosphere in Egypt,

the colours, where they have not been purposely damaged.

1 Champollion, Lettres, 380, et seqq. It mav perhaps conduce to perspicuity, or at least serve to prevent mistakes, if we introduce

here the eight reigns anterior to that of Ithamses-Meiamoun, in their chronological order. They stand thus : 1. Amenophis II. or

Memnon ; 2. Horus ; 3. Rhamses I.; 4. Menephtha 1. or Ousirei; 5. llhamses the Great, or Sesostris ; 6. Menephtha II.; 7. Me¬

nephtha III.; 8. Rhamerreh ; and, 9- Ithamses-Meiamoun. The monuments of different orders having clearly demonstrated that

Rhamses the Great, the Sesostris of Herodotus, must be included in the eighteenth dynasty, as answering exactly to the Rhamses

called Mgyptus in the extracts of Manetho, it follows that in Rhamses-Meiamoun, the Rhamses-Sethos of the same lists of Manetho,

we recognise the head or chief of the nineteenth dynasty.

1 The following is Manetho’s catalogue of the Hiospolitan dynasties and kings.

XVIII. Dynasty- Diospolitan.

Years. B. C.

1. Thouthmosis or Amosis, reigned 24 1874

2. Chebron his son 13 1750

3. Amenophthis 20 1737

4. Ammosis, sister 18 1717

5. Mesphres, son 16 1699

6. Misphragmuthosis 23 1683

7- Thmosis or Thouthmosis, s 9 1660

8. Amenophis, s. (Memnon) 31 1651

9. Horus, s 41 1620

10. Acenchres, d 23 1579

11. Rathotis, sist 15 1556

12. Acencheres, s 17 1541

13. Acencheres II. s 11 1524

14. Armais 6 1513

Years.

15. Ramesses or Rhamses s. \ nj!

16. Armesses Meiamoun, s . f

17- Amenophis or Amenophth 15

B. C.

1507

1439

XIX. Dynasty. Diospolitan.

18. Rhamses the Great or Sesostris 53 ■

19. Rapasces 63

20. Ammenophthes \ #;n

21. Rameses or llhamses J

22. ' Ammenemes 15

23. Thuoris 7

XX. Dynasty. Diospolitan.

24...35. Twelve kings 125

1424

1371

1308

1248

1233

1226

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 8, DIA-England > (549) Page 539 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193330142 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|