Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 15, NIC-PAR

(238) Page 218

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

21 8

OfYisior. ^ da will be the

optics.

m a u vvm ray refracted by the first lens.

Through the focus of the second lens draw the perpen¬

dicular^ e, cutting AB in *; and draw e b through the

centre of the second lens. BD parallel to b e will be

the next refracted ray. Through the focus * of the

third lens draw the perpendicular */, cutting in/,

and draw f c through the centre of the third lens. ^

parallel to/c, will be the refracted ray } and so on.

Sect. V. On Vision.

Having described how the rays of light, flowing from

obiects, and passing through convex glasses, are collect¬

ed into points, and form the images of external objects ,

it will be easy to understand how the rays are refracted

by the humours of the eye, and are thereby collected

into innumerable points on the retina on which they

form the images of the objects from which they flow.

For the different humours of the eye, and particularly

or uie — ^ ' - i #

the crystalline, are to be considered as a convex glass,

and the rays in passing through them as affected in t ic

same manner in the one as in the other. A description

of the coats and humours, &c. has been given in Ana¬

tomy ; but it will be proper to repeat as much of

the description as will be sufficient for our present pur-

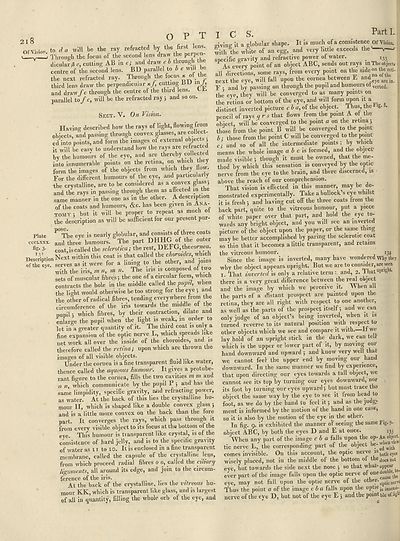

Plate 1 The eye is nearly globular, and consists of three coats

ccclxxx. an(l three humours. The part UHHG of the ou er

fig‘ 3' coat, is called the sclerotica ; the rest, DEFG, the cornea

Description Next within this coat is that caJW the cW« »Wh

of the eye. serves as it were for a lining to the other, and joins

with the iris, m n, m n. The iris is composed of two

sets of muscular fibres-, the one of a circular form, which

contracts the bole in the middle called the pupil, when

the light would otherwise be too strong for the eye-, and

the other of radical fibres, tending everywhere from the

circumference of the iris towards the middle of the

pupil j which fibres, bv their contraction, dilate and

enlarge the pupil when the light is weak, m order to

let in a greater quantity of it. The third coat is only a

fine expansion of the optic nerve L, which spreads lute

net work all over the inside of the choroides, and is

theiefore called the retrna; upon which are thrown the

images of all visible objects.

Under the cornea is a fine transparent fluid like water,

thence called the aqueous humour. It gives a protube¬

rant figure to the cornea, fills the two cavities m m and

n n which communicate by the pupil P \ and has the

same limpidity, specific gravity, and refracting power,

as water. At the back of this lies the crystalline hu¬

mour II, which is shaped like a double convex glass ;

and is a little more convex on the back than the fore

part. It converges the rays, which pass through it

from every visible object to its focus at tho bottom of the

eye> This humour is transparent like crystal, is of the

consistence of hard jelly, and is to the specific gravity

of water as 11 to xo. It is enclosed in a fine transparent

membrane, called the capsule of the crystalline lens,

from which proceed radial fibres o o, called the ciliary

ligaments, all around its edge, and join to the circum¬

ference of the iris.

At the back of the crystalline, lies the vitreous hu¬

mour KK, which is transparent like glass, and is largest

of all in quantity, filling the whole orb of the eye, and

Part L

giving it a globular shape. It is much of a consistence Of Vision,

with the white of an egg, and very little exceeds the' y J

specific gravity and refractive power of water. _ ^

As every point of an object ABC, sends out rays in The objects

all directions, some rays, from every point on the side on the ret.

next the eye, will fall upon the cornea between E and ^

;p . and by passing on through the pupil and humours ot verle(j.

the eye they will be converged to as many points on

the retina or bottom of the eye, and will form upon it a

distinct inverted picture c b a, of the object. Thus, the o- •

pencil of rays q r s that flows from the point A of the

object, will be converged to the point a on the retina -,

those from the point B will be converged to the point

b; those from the point C will be converged to the point

c; and so of all the intermediate points : by which

means the whole image a 6 c is formed, and the object-

made visible ", though it must be owned, that the me¬

thod by which this sensation is conveyed by the optic

nerve from the eye to the brain, and there discerned, is

above the reach of our comprehension.

That vision is effected in this manner, may be de¬

monstrated experimentally. Take a bullock’s eye whilst

it is fresh 5 and having cut off the three coats from the

back part, quite to the vitreous humour, put a piece

of white paper over that part, and hold the eye to¬

wards any bright object, and you will see an inverted

picture of the object upon the paper, or the same thing

may be better accomplished by paring the sclerotic coat

so thin that it becomes a little transparent, and retains

the vitreous humour. 134

Since the image is inverted, many have wondered why the?

why the object appears upright. But we are to consider, are seen

1. That inverted is only a relative term : and, 2, l hat 1 k

there is a very great difference between the real object

and the image by which we perceive it. When all

the parts of a distant prospect are painted upon the

retina, they are all right with respect to one another,

as well as the parts of the prospect itself-, and we can

only judge of an object’s being inverted, when it is

turned reverse to its natural position with respect to

other objects which we see and compare it with.—If we

lay hold of an upright stick in the dark, we can tell

which is the upper or lower part of it, by moving oui

hand downward and upward 3 and know very well that

we cannot feel the upper end by moving our hand

downward. In the same manner we find by experience,

that upon directing our eyes towards a tall object, we

cannot see its top by turning our eyes downward, nor

its foot by turning our eyes upward; but must trace the

object the same way by the eye to see it irom bead to

foot, as we do by the hand to feel it; and as the judgy

ment is informed by the motion ot the hand in one case*

so it is also by the motion of the eye in the other.

In fig. 9. is exhibited the manner of seeing the same Fig. <?•

object ABC, by both the eyes D and E at once. 135

When any part of the image cb a falls upon the °p-A»

tic nerve E,. the corresponding part of the object be-”™

* ~ o\ 11 nf rtiFtir*. nerve 18. .1 „

comes invisible. On this account, the optic nerve is'both eyeS

wisely placed, not in the middle of the bottom ol the(joe9not

eye, but towards the side next the nose ; so that what-appear

ever part of the image falls upon the optic nerve °f one^e’he'

eye, may not fall upon the optic nerve of the otbci'-oplicnerve

Thus the point a of the image eba falls upon the opticis insensi.

nerve of the eye D, but not of the eye E ; and the point ble of.tig

OfYisior. ^ da will be the

optics.

m a u vvm ray refracted by the first lens.

Through the focus of the second lens draw the perpen¬

dicular^ e, cutting AB in *; and draw e b through the

centre of the second lens. BD parallel to b e will be

the next refracted ray. Through the focus * of the

third lens draw the perpendicular */, cutting in/,

and draw f c through the centre of the third lens. ^

parallel to/c, will be the refracted ray } and so on.

Sect. V. On Vision.

Having described how the rays of light, flowing from

obiects, and passing through convex glasses, are collect¬

ed into points, and form the images of external objects ,

it will be easy to understand how the rays are refracted

by the humours of the eye, and are thereby collected

into innumerable points on the retina on which they

form the images of the objects from which they flow.

For the different humours of the eye, and particularly

or uie — ^ ' - i #

the crystalline, are to be considered as a convex glass,

and the rays in passing through them as affected in t ic

same manner in the one as in the other. A description

of the coats and humours, &c. has been given in Ana¬

tomy ; but it will be proper to repeat as much of

the description as will be sufficient for our present pur-

Plate 1 The eye is nearly globular, and consists of three coats

ccclxxx. an(l three humours. The part UHHG of the ou er

fig‘ 3' coat, is called the sclerotica ; the rest, DEFG, the cornea

Description Next within this coat is that caJW the cW« »Wh

of the eye. serves as it were for a lining to the other, and joins

with the iris, m n, m n. The iris is composed of two

sets of muscular fibres-, the one of a circular form, which

contracts the bole in the middle called the pupil, when

the light would otherwise be too strong for the eye-, and

the other of radical fibres, tending everywhere from the

circumference of the iris towards the middle of the

pupil j which fibres, bv their contraction, dilate and

enlarge the pupil when the light is weak, m order to

let in a greater quantity of it. The third coat is only a

fine expansion of the optic nerve L, which spreads lute

net work all over the inside of the choroides, and is

theiefore called the retrna; upon which are thrown the

images of all visible objects.

Under the cornea is a fine transparent fluid like water,

thence called the aqueous humour. It gives a protube¬

rant figure to the cornea, fills the two cavities m m and

n n which communicate by the pupil P \ and has the

same limpidity, specific gravity, and refracting power,

as water. At the back of this lies the crystalline hu¬

mour II, which is shaped like a double convex glass ;

and is a little more convex on the back than the fore

part. It converges the rays, which pass through it

from every visible object to its focus at tho bottom of the

eye> This humour is transparent like crystal, is of the

consistence of hard jelly, and is to the specific gravity

of water as 11 to xo. It is enclosed in a fine transparent

membrane, called the capsule of the crystalline lens,

from which proceed radial fibres o o, called the ciliary

ligaments, all around its edge, and join to the circum¬

ference of the iris.

At the back of the crystalline, lies the vitreous hu¬

mour KK, which is transparent like glass, and is largest

of all in quantity, filling the whole orb of the eye, and

Part L

giving it a globular shape. It is much of a consistence Of Vision,

with the white of an egg, and very little exceeds the' y J

specific gravity and refractive power of water. _ ^

As every point of an object ABC, sends out rays in The objects

all directions, some rays, from every point on the side on the ret.

next the eye, will fall upon the cornea between E and ^

;p . and by passing on through the pupil and humours ot verle(j.

the eye they will be converged to as many points on

the retina or bottom of the eye, and will form upon it a

distinct inverted picture c b a, of the object. Thus, the o- •

pencil of rays q r s that flows from the point A of the

object, will be converged to the point a on the retina -,

those from the point B will be converged to the point

b; those from the point C will be converged to the point

c; and so of all the intermediate points : by which

means the whole image a 6 c is formed, and the object-

made visible ", though it must be owned, that the me¬

thod by which this sensation is conveyed by the optic

nerve from the eye to the brain, and there discerned, is

above the reach of our comprehension.

That vision is effected in this manner, may be de¬

monstrated experimentally. Take a bullock’s eye whilst

it is fresh 5 and having cut off the three coats from the

back part, quite to the vitreous humour, put a piece

of white paper over that part, and hold the eye to¬

wards any bright object, and you will see an inverted

picture of the object upon the paper, or the same thing

may be better accomplished by paring the sclerotic coat

so thin that it becomes a little transparent, and retains

the vitreous humour. 134

Since the image is inverted, many have wondered why the?

why the object appears upright. But we are to consider, are seen

1. That inverted is only a relative term : and, 2, l hat 1 k

there is a very great difference between the real object

and the image by which we perceive it. When all

the parts of a distant prospect are painted upon the

retina, they are all right with respect to one another,

as well as the parts of the prospect itself-, and we can

only judge of an object’s being inverted, when it is

turned reverse to its natural position with respect to

other objects which we see and compare it with.—If we

lay hold of an upright stick in the dark, we can tell

which is the upper or lower part of it, by moving oui

hand downward and upward 3 and know very well that

we cannot feel the upper end by moving our hand

downward. In the same manner we find by experience,

that upon directing our eyes towards a tall object, we

cannot see its top by turning our eyes downward, nor

its foot by turning our eyes upward; but must trace the

object the same way by the eye to see it irom bead to

foot, as we do by the hand to feel it; and as the judgy

ment is informed by the motion ot the hand in one case*

so it is also by the motion of the eye in the other.

In fig. 9. is exhibited the manner of seeing the same Fig. <?•

object ABC, by both the eyes D and E at once. 135

When any part of the image cb a falls upon the °p-A»

tic nerve E,. the corresponding part of the object be-”™

* ~ o\ 11 nf rtiFtir*. nerve 18. .1 „

comes invisible. On this account, the optic nerve is'both eyeS

wisely placed, not in the middle of the bottom ol the(joe9not

eye, but towards the side next the nose ; so that what-appear

ever part of the image falls upon the optic nerve °f one^e’he'

eye, may not fall upon the optic nerve of the otbci'-oplicnerve

Thus the point a of the image eba falls upon the opticis insensi.

nerve of the eye D, but not of the eye E ; and the point ble of.tig

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 15, NIC-PAR > (238) Page 218 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/192584792 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.11 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|