Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 7, ETM-GOA

(62) Page 46 - EXC

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

E X C

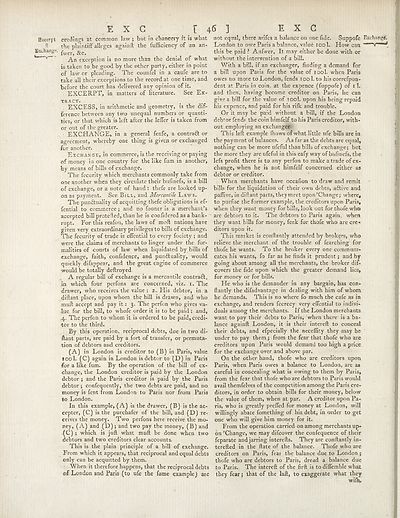

B-xcerpt ceedings at common law ; but in chancery it is what

II the plaintiff alleges againff the fufficiency of an an-

fwer, &c.

^ An exception is no more than the denial of what

is taken to be good by the other party, either in point

of law or pleading. The counfel in a caufe are to

take all their exceptions to the record at one time, and

before the court has delivered any opinion of it.

EXCERPT, in matters of literature. See Ex¬

tract.

EXCESS, in arithmetic and geometry, is the dif¬

ference between any two unequal numbers or quanti¬

ties, or that which is left after the leffer is taken from

or out of the greater.

EXCHANGE, in a general fenfe, a contraft or

agreement, whereby one thing is given or exchanged

for another.

Exchange, in commerce, is the receiving or paying

of money in one country for the like fum in another,

by means of bills of exchange.

The fecurity which merchants commonly take from

one another when they circulate their bufinefs, is a bill

of exchange, or a note of hand : thefe are looked up¬

on as payment. See Bill, and Mercantile Laws.

The punctuality of acquitting thefe obligations is ef-

fential to commerce; and no fooner is a merchant’s

accepted billprotetled, than he is confidered as a bank- ~

rupt. For this reafon, the laws of mod nation^ have

given very extraordinary privileges to bills of exchange.

The fecurity of trade is effential to every fociety ; and

were the claims of merchants to linger under the for¬

malities of courts of law when liquidated by hills of

exchange, faith, confidence, and punctuality, would

quickly difappear, and the great engine of commerce

would be totally deftroyed

A regular bill of exchange is a mercantile contraCt,

in which four perfons are concerned, viz. i. The

drawer, who receives the value : 2. His debtor, in a

diftant place, upon whom the bill is drawn, and who

muff accept and pay it: 3. The perfon who gives va¬

lue for the bill, to whofe order it is to be paid : and,

4. The perfon to whom it is ordered to be paid, credi¬

tor to the third.

By this operation, reciprocal debts, due in two di¬

ftant parts, are paid by a fort of transfer, or permuta¬

tion of debtors and creditors.

(A) in London is creditor to (B) in Paris, value

*001. (C) again in London is debtor to (D) in Paris

for a like fum. By the operation of the bill of ex¬

change, the London creditor is paid by the London

debtor ; and the Paris creditor is paid by the Paris

debtor; confequently, the two debts are paid, and no

money is fent from London to Paris nor from Paris

to London.

In this example, (A) is the drawer, (B) is the ac¬

cepter, (C) is the purchafer of the bill, and (D) re¬

ceives the money. Two perfons here receive the mo¬

ney, (A) and (D); and two pay the money, (B) and

{C) ; which is juft what muff be done when two

debtors and two creditors clear accounts.

This is the plain principle of a bill of exchange.

From which it appears, that reciprocal and equal debts

only can be acquitted by them.

When it therefore happens, that the reciprocal debts

of London and Paris (to ufe the fame example) are

E X G

not equal, there arifes a balance on one fide. Suppofe

London to owe Paris a balance, value 1001. How can

this be paid ? Anfwer, It may either be done with or

without the intervention of a bill.

With a bill, if an exchanger, finding a demand for

a bill upon Paris for the value of 100I. when Paris

owes no more to London, fends lool. to his correfpon-

dent at Paris in coin, at the expence (fuppofe) of 1 I.

and then, having become creditor on Paris, he can

give a bill for the value of 100I. upon his being repaid

his expence, and paid for his rilk and trouble.

Or it may be paid without a bill, if the London

debtor fends the coin bimfelf to his Paris creditor, with¬

out employing an exchanger

This laft example (hows of what little ufe bills are in

the payment of balances. As far as the debts are equal,

nothing can be more ufeful than bills of exchange; but

the more they are ufeful in this eafy way of bufinefs, the \ I

lefs profit there is to any perfon to make a trade of ex¬

change, when he is not himfelf concerned either as

debtor or creditor.

When merchants have occafion to draw and remit

bills for the liquidation of their own debts, active and

paffive, in diftant parts, they meet upon’Change; where,

to purfue the former example, the creditors upon Paris,

when they want money for bills, look out for thofe who

are debtors to it. The debtors to Paris again, when

they want bills for money, feek for thofe who are cre¬

ditors upon it.

This market is conftantly attended by brokers, who

relieve the merchant of the trouble of fearching for

thofe he wants. To the broker every one communi¬

cates his wants, fo far as he finds it prudent; and by

going about among all the merchants, the broker dif-

covers the fide upon which the greater demand lies,

for money or for bills.

He who is the demander in any bargain, has con¬

ftantly the difadvantage in dealing with him of whom

he demands. This is no where fo much the cafe as in

exchange, and renders fecrecy very effential to indivi¬

duals among the merchants. If the London merchants

want to pay their debts to Paris, when there is a ba¬

lance againft London, it is their intereft to conceal

their debts, and efpecially the neceffity they may be

under to pay them; from the fear that thofe who are

creditors upon Paris would demand too high a price

for the exchange over and above par.

On the other hand, thofe who are creditors upon

Paris, when Paris owes a balance to London, are as

careful in concealing what is owing to them by Paris,

from the fear that rhofe who are debtors to Paris would

avail themfelves of the competition among the Paris cre¬

ditors, in order to obtain bills for their money, below

the value of them, when at par. A creditor upon Pa¬

ris, who is greatly preffed for money at London, will

willingly abate fomething of his debt, in order to get

one who will give him money for it.

From the operation carried on among merchants up¬

on ’Change, we may difcover the confequence of their

feparate and jarring interefts. They are conftantly in-

terefted in the ftate of the balance. Thofe who are

creditors on Paris, fear the balance due to London ;

thofe who are debtors to Paris, dread a balance due

to Paris. The intereft of the firft is to diffemble what

they fear; that of the laft, to exaggerate what they

wilh.

r 46 1

B-xcerpt ceedings at common law ; but in chancery it is what

II the plaintiff alleges againff the fufficiency of an an-

fwer, &c.

^ An exception is no more than the denial of what

is taken to be good by the other party, either in point

of law or pleading. The counfel in a caufe are to

take all their exceptions to the record at one time, and

before the court has delivered any opinion of it.

EXCERPT, in matters of literature. See Ex¬

tract.

EXCESS, in arithmetic and geometry, is the dif¬

ference between any two unequal numbers or quanti¬

ties, or that which is left after the leffer is taken from

or out of the greater.

EXCHANGE, in a general fenfe, a contraft or

agreement, whereby one thing is given or exchanged

for another.

Exchange, in commerce, is the receiving or paying

of money in one country for the like fum in another,

by means of bills of exchange.

The fecurity which merchants commonly take from

one another when they circulate their bufinefs, is a bill

of exchange, or a note of hand : thefe are looked up¬

on as payment. See Bill, and Mercantile Laws.

The punctuality of acquitting thefe obligations is ef-

fential to commerce; and no fooner is a merchant’s

accepted billprotetled, than he is confidered as a bank- ~

rupt. For this reafon, the laws of mod nation^ have

given very extraordinary privileges to bills of exchange.

The fecurity of trade is effential to every fociety ; and

were the claims of merchants to linger under the for¬

malities of courts of law when liquidated by hills of

exchange, faith, confidence, and punctuality, would

quickly difappear, and the great engine of commerce

would be totally deftroyed

A regular bill of exchange is a mercantile contraCt,

in which four perfons are concerned, viz. i. The

drawer, who receives the value : 2. His debtor, in a

diftant place, upon whom the bill is drawn, and who

muff accept and pay it: 3. The perfon who gives va¬

lue for the bill, to whofe order it is to be paid : and,

4. The perfon to whom it is ordered to be paid, credi¬

tor to the third.

By this operation, reciprocal debts, due in two di¬

ftant parts, are paid by a fort of transfer, or permuta¬

tion of debtors and creditors.

(A) in London is creditor to (B) in Paris, value

*001. (C) again in London is debtor to (D) in Paris

for a like fum. By the operation of the bill of ex¬

change, the London creditor is paid by the London

debtor ; and the Paris creditor is paid by the Paris

debtor; confequently, the two debts are paid, and no

money is fent from London to Paris nor from Paris

to London.

In this example, (A) is the drawer, (B) is the ac¬

cepter, (C) is the purchafer of the bill, and (D) re¬

ceives the money. Two perfons here receive the mo¬

ney, (A) and (D); and two pay the money, (B) and

{C) ; which is juft what muff be done when two

debtors and two creditors clear accounts.

This is the plain principle of a bill of exchange.

From which it appears, that reciprocal and equal debts

only can be acquitted by them.

When it therefore happens, that the reciprocal debts

of London and Paris (to ufe the fame example) are

E X G

not equal, there arifes a balance on one fide. Suppofe

London to owe Paris a balance, value 1001. How can

this be paid ? Anfwer, It may either be done with or

without the intervention of a bill.

With a bill, if an exchanger, finding a demand for

a bill upon Paris for the value of 100I. when Paris

owes no more to London, fends lool. to his correfpon-

dent at Paris in coin, at the expence (fuppofe) of 1 I.

and then, having become creditor on Paris, he can

give a bill for the value of 100I. upon his being repaid

his expence, and paid for his rilk and trouble.

Or it may be paid without a bill, if the London

debtor fends the coin bimfelf to his Paris creditor, with¬

out employing an exchanger

This laft example (hows of what little ufe bills are in

the payment of balances. As far as the debts are equal,

nothing can be more ufeful than bills of exchange; but

the more they are ufeful in this eafy way of bufinefs, the \ I

lefs profit there is to any perfon to make a trade of ex¬

change, when he is not himfelf concerned either as

debtor or creditor.

When merchants have occafion to draw and remit

bills for the liquidation of their own debts, active and

paffive, in diftant parts, they meet upon’Change; where,

to purfue the former example, the creditors upon Paris,

when they want money for bills, look out for thofe who

are debtors to it. The debtors to Paris again, when

they want bills for money, feek for thofe who are cre¬

ditors upon it.

This market is conftantly attended by brokers, who

relieve the merchant of the trouble of fearching for

thofe he wants. To the broker every one communi¬

cates his wants, fo far as he finds it prudent; and by

going about among all the merchants, the broker dif-

covers the fide upon which the greater demand lies,

for money or for bills.

He who is the demander in any bargain, has con¬

ftantly the difadvantage in dealing with him of whom

he demands. This is no where fo much the cafe as in

exchange, and renders fecrecy very effential to indivi¬

duals among the merchants. If the London merchants

want to pay their debts to Paris, when there is a ba¬

lance againft London, it is their intereft to conceal

their debts, and efpecially the neceffity they may be

under to pay them; from the fear that thofe who are

creditors upon Paris would demand too high a price

for the exchange over and above par.

On the other hand, thofe who are creditors upon

Paris, when Paris owes a balance to London, are as

careful in concealing what is owing to them by Paris,

from the fear that rhofe who are debtors to Paris would

avail themfelves of the competition among the Paris cre¬

ditors, in order to obtain bills for their money, below

the value of them, when at par. A creditor upon Pa¬

ris, who is greatly preffed for money at London, will

willingly abate fomething of his debt, in order to get

one who will give him money for it.

From the operation carried on among merchants up¬

on ’Change, we may difcover the confequence of their

feparate and jarring interefts. They are conftantly in-

terefted in the ftate of the balance. Thofe who are

creditors on Paris, fear the balance due to London ;

thofe who are debtors to Paris, dread a balance due

to Paris. The intereft of the firft is to diffemble what

they fear; that of the laft, to exaggerate what they

wilh.

r 46 1

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 7, ETM-GOA > (62) Page 46 - EXC |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/189122035 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|