Blair Collection > Celtic studies

(40)

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

10 I ntvod action.

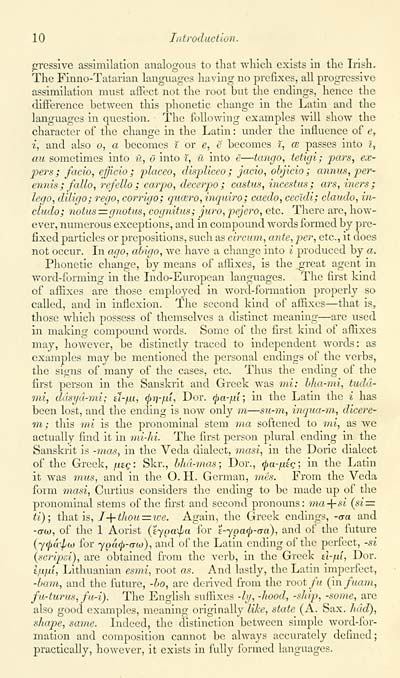

gressive assimilation analogous to that -whicli exists in tlie Irish.

The Finno-Tatarian languages having no prefixes, all progressive

assimilation must affect not the root but the endings, hence the

difference between this phonetic change in the Latin and the

languages in question. The following examples will show the

character of the change in the Latin : under the influence of e,

i, and also o, a becomes t or e, e becomes i, ce passes into I,

au sometimes into n, o into t, u into e — tango, tetigi; pars, ex-

pers ; facio, ejicio ; placeo, displiceo ; jacio, objicio; annus, per-

ennis ; folio, refello ; carpo, decerpo ; castiis, incestus ; ars, iners ;

lego, diligo; rego, corrigo; qucero, inqidro; caedo, cec'idi; claudo, in-

clude; notus:=ignotus, cognitiis; jura, pejero, etc. There are, how-

ever, numerous exceptions, and in compound words formed by pre-

fixed particles or prepositions, such as circum, ante, per, etc., it does

not occur. In ago, abigo, we have a change into i produced by a.

Phonetic change, by means of affixes, is the ^reat agent in

word-forming in the Indo-European languages. The first kind

of affixes are those employed in word-formation properly so

called, and in inflexion. The second kind of affixes — that is,

those which possess of themselves a distinct meaning — are used

in making compound words. Some of the first kind of affixes

may, however, be distinctly traced to independent words: as

examples may be mentioned the personal endings of the verbs,

the signs of many of the cases, etc. Thus the ending of the

first person in the Sanskrit and Greek was mi: blia-mi, tudd-

mi, ddsyd-mi; il-fxi, ^r]-fii, Dor. <j)a-fxi; in the Latin the i has

been lost, and the ending is now only m — sii-i7i, inqua-ni, dicere-

m; this mi is the pronominal stem ma softened to mi, as we

actually find it in mi-hi. The first person plural ending in the

Sanskrit is -mas, in the Veda dialect, masi, in the Doric dialect

of the Greek, juag: Skr., bhd-mas; Dor., (^ta-fiiq; in the Latin

it was mus, and in the O. H. German, mes. From the Veda

form masi, Curtius considers the ending to be made up of the

pronominal stems of the first and second pronouns: ??ia+si (si=:

ti); that is, J-^thou = tce. Again, the Greek endings, -aa and

-o-w, of the 1 Aorist (£y^>a^a for E-ypa^-o-a), and of the future

{y(f>a'^(x) for ypa^-o-w), and of the Latin ending of the perfect, -si

{scripd), are obtained from the verb, in the Greek ti-ij.i, Dor.

Ijufxi, Lithuanian esmi, root as. And lastly, the Latin imperfect,

-ba7n, and the future, -bo, arc derived from the root/?* (infiunn,

fu-turus, fu-i). The English suffixes -Ig, -hood, -ship, -some, are

also good examples, meaning originally like, state (A. Sax. had),

shape, same. Indeed, the distinction between simple word-for-

mation and composition cannot be always accurately defined;

practically, however, it exists in fully formed languages.

gressive assimilation analogous to that -whicli exists in tlie Irish.

The Finno-Tatarian languages having no prefixes, all progressive

assimilation must affect not the root but the endings, hence the

difference between this phonetic change in the Latin and the

languages in question. The following examples will show the

character of the change in the Latin : under the influence of e,

i, and also o, a becomes t or e, e becomes i, ce passes into I,

au sometimes into n, o into t, u into e — tango, tetigi; pars, ex-

pers ; facio, ejicio ; placeo, displiceo ; jacio, objicio; annus, per-

ennis ; folio, refello ; carpo, decerpo ; castiis, incestus ; ars, iners ;

lego, diligo; rego, corrigo; qucero, inqidro; caedo, cec'idi; claudo, in-

clude; notus:=ignotus, cognitiis; jura, pejero, etc. There are, how-

ever, numerous exceptions, and in compound words formed by pre-

fixed particles or prepositions, such as circum, ante, per, etc., it does

not occur. In ago, abigo, we have a change into i produced by a.

Phonetic change, by means of affixes, is the ^reat agent in

word-forming in the Indo-European languages. The first kind

of affixes are those employed in word-formation properly so

called, and in inflexion. The second kind of affixes — that is,

those which possess of themselves a distinct meaning — are used

in making compound words. Some of the first kind of affixes

may, however, be distinctly traced to independent words: as

examples may be mentioned the personal endings of the verbs,

the signs of many of the cases, etc. Thus the ending of the

first person in the Sanskrit and Greek was mi: blia-mi, tudd-

mi, ddsyd-mi; il-fxi, ^r]-fii, Dor. <j)a-fxi; in the Latin the i has

been lost, and the ending is now only m — sii-i7i, inqua-ni, dicere-

m; this mi is the pronominal stem ma softened to mi, as we

actually find it in mi-hi. The first person plural ending in the

Sanskrit is -mas, in the Veda dialect, masi, in the Doric dialect

of the Greek, juag: Skr., bhd-mas; Dor., (^ta-fiiq; in the Latin

it was mus, and in the O. H. German, mes. From the Veda

form masi, Curtius considers the ending to be made up of the

pronominal stems of the first and second pronouns: ??ia+si (si=:

ti); that is, J-^thou = tce. Again, the Greek endings, -aa and

-o-w, of the 1 Aorist (£y^>a^a for E-ypa^-o-a), and of the future

{y(f>a'^(x) for ypa^-o-w), and of the Latin ending of the perfect, -si

{scripd), are obtained from the verb, in the Greek ti-ij.i, Dor.

Ijufxi, Lithuanian esmi, root as. And lastly, the Latin imperfect,

-ba7n, and the future, -bo, arc derived from the root/?* (infiunn,

fu-turus, fu-i). The English suffixes -Ig, -hood, -ship, -some, are

also good examples, meaning originally like, state (A. Sax. had),

shape, same. Indeed, the distinction between simple word-for-

mation and composition cannot be always accurately defined;

practically, however, it exists in fully formed languages.

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Early Gaelic Book Collections > Blair Collection > Celtic studies > (40) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/75771622 |

|---|

| Description | A selection of books from a collection of more than 500 titles, mostly on religious and literary topics. Also includes some material dealing with other Celtic languages and societies. Collection created towards the end of the 19th century by Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray. |

|---|

| Description | Selected items from five 'Special and Named Printed Collections'. Includes books in Gaelic and other Celtic languages, works about the Gaels, their languages, literature, culture and history. |

|---|