480

persuaded that nothing could be given either so

entertaining or so full of information.

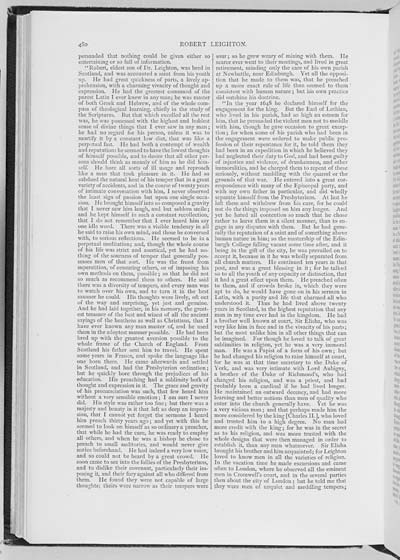

"Robert, eldest son of Dr. Leighton, was bred in

Scotland, and was accounted a saint from his youth

up. He had great quickness of parts, a lively ap-

prehension, with a charming vivacity of thought and

expression. He had the greatest command of the

purest Latin I ever knew in any man; he was master

of both Greek and Hebrew, and of the whole com-

pass of theological learning, chiefly in the study of

the Scriptures. But that which excelled all the rest

was, he was possessed with the highest and boldest

sense of divine things that I ever saw in any man;

he had no regard for his person, unless it was to

mortify it by a constant low diet, that was like a

perpetual fast. He had both a contempt of wealth

and reputation: he seemed to have the lowest thoughts

of himself possible, and to desire that all other per-

sons should think as meanly of him as he did him-

self. He bore all sorts of ill usage and reproach

like a man that took pleasure in it. He had so

subdued the natural heat of his temper that in a great

variety of accidents, and in the course of twenty years

of intimate conversation with him, I never observed

the least sign of passion but upon one single occa-

sion. He brought himself into so composed a gravity

that I never saw him laugh, and but seldom smile;

and he kept himself in such a constant recollection,

that I do not remember that I ever heard him say

one idle word. There was a visible tendency in all

he said to raise his own mind, and those he conversed

with, to serious reflections. He seemed to be in a

perpetual meditation; and, though the whole course

of his life was strict and ascetical, yet he had no-

thing of the sourness of temper that generally pos-

sesses men of that sort. He was the freest from

superstition, of censuring others, or of imposing his

own methods on them, possible; so that he did not

so much as recommend them to others. He said

there was a diversity of tempers, and every man was

to watch over his own, and to turn it in the best

manner he could. His thoughts were lively, oft out

of the way and surprising, yet just and genuine.

And he had laid together, in his memory, the great-

est treasure of the best and wisest of all the ancient

sayings of the heathens as well as Christians, that I

have ever known any man master of, and he used

them in the adeptest manner possible. He had been

bred up with the greatest aversion possible to the

whole frame of the Church of England. From

Scotland his father sent him to travel. He spent

some years in France, and spoke the language like

one born there. He came afterwards and settled

in Scotland, and had the Presbyterian ordination;

but he quickly bore through the prejudices of his

education. His preaching had a sublimity both of

thought and expression in it. The grace and gravity

of his pronunciation was such, that few heard him

without a very sensible emotion; I am sure I never

did. His style was rather too fine; but there was a

majesty and beauty in it that left so deep an impres-

sion, that I cannot yet forget the sermons I heard

him preach thirty years ago; and yet with this he

seemed to look on himself as so ordinary a preacher,

that while he had the cure, he was ready to employ

all others, and when he was a bishop he chose to

preach to small auditories, and would never give

notice beforehand. He had indeed a very low voice,

and so could not be heard by a great crowd. He

soon came to see into the follies of the Presbyterians,

and to dislike their covenant, particularly their im-

posing it, and their fury against all who differed from

them. He found they were not capable of large

thoughts; theirs were narrow as their tempers were

sour; so he grew weary of mixing with them. He

scarce ever went to their meetings, and lived in great

retirement, minding only the care of his own parish

at Newbattle, near Edinburgh. Yet all the opposi-

tion that he made to them was, that he preached

up a more exact rule of life than seemed to them

consistent with human nature; but his own practice

did outshine his doctrine.

"In the year 1648 he declared himself for the

engagement for the king. But the Earl of Lothian,

who lived in his parish, had so high an esteem for

him, that he persuaded the violent men not to meddle

with him, though he gave occasion to great excep-

tion ; for when some of his parish who had been in

the engagement were ordered to make public pro-

fession of their repentance for it, he told them they

had been in an expedition in which he believed they

had neglected their duty to God, and had been guilty

of injustice and violence, of drunkenness, and other

immoralities, and he charged them to repent of these

seriously, without meddling with the quarrel or the

grounds of that war. He entered into a great cor-

respondence with many of the Episcopal party, and

with my own father in particular, and did wholly

separate himself from the Presbyterians. At last he

left them and withdrew from his cure, for he could

not do the things imposed on him any longer. And

yet he hated all contention so much that he chose

rather to leave them in a silent manner, than to en-

gage in any disputes with them. But he had gene-

rally the reputation of a saint and of something above

human nature in him; so the mastership of the Edin-

burgh College falling vacant some time after, and it

being in the gift of the city, he was prevailed on to

accept it, because in it he was wholly separated from

all church matters. He continued ten years in that

post, and was a great blessing in it; for he talked

so to all the youth of any capacity or distinction, that

it had a great effect upon them. He preached often

to them, and if crowds broke in, which they were

apt to do, he would have gone on in his sermon in

Latin, with a purity and life that charmed all who

understood it. Thus he had lived above twenty

years in Scotland, in the highest reputation that any

man in my time ever had in the kingdom. He had

a brother well known at court, Sir Elisha, who was

very like him in face and in the vivacity of his parts;

but the most unlike him in all other things that can

be imagined. For though he loved to talk of great

sublimities in religion, yet he was a very immoral

man. He was a Papist of a form of his own; but

he had changed his religion to raise himself at court,

for he was at that time secretary to the Duke of

York, and was very intimate with Lord Aubigny,

a brother of the Duke of Richmond's, who had

changed his religion, and was a priest, and had

probably been a cardinal if he had lived longer.

He maintained an outward decency, and had more

learning and better notions than men of quality who

enter into the church generally have. Yet he was

a very vicious man; and that perhaps made him the

more considered by the king [Charles II.], who loved

and trusted him to a high degree. No man had

more credit with the king; for he was in the secret

as to his religion, and was more trusted with the

whole designs that were then managed in order to

establish it, than any man whatsoever. Sir Elisha

brought his brother and him acquainted; for Leighton

loved to know men in all the varieties of religion.

In the vacation time he made excursions and came

often to London, where he observed all the eminent

men in Cromwell's court, and in the several parties

then about the city of London; but he told me that

they were men of unquiet and meddling tempers;

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

![]()