Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

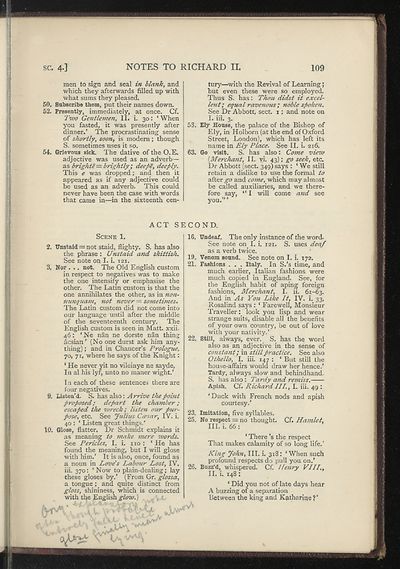

sc. 4-]

NOTES TO RICHARD II.

109

men to sign and seal in blank, and

which they afterwards filled up with

what sums they pleased.

50. Subscribe them, put their names down.

52. Presently, immediately, at once. Cf.

Two Gentlemen, II. i. 30: ‘When

you fasted, it was presently after

dinner.' The procrastinating sense

of shortly, soon, is modern; though

S. sometimes uses it so.

54. Grievous sick. The dative oftheO.E.

adjective was used as an adverb—

as brighte =■ brightly; deepe, deeply.

This e was dropped; and then it

appeared as if any adjective could

be used as an adverb. This could

never have been the case with words

that came in—in the sixteenth cen-

53.

63.

tury—with the Revival of Learning;

but even these were so employed.

Thus S. has: Thou didst it excel¬

lent; equal ravenous ; noble spoken.

See Dr Abbott, sect. 1; and note on

I. iii. 3.

Ely House, the palace of the Bishop of

Ely, in Holborn (at the end of Oxford

Street, London), which has left its

name in Ely Place. See II. i. 216.

Go visit. S. has also: Come view

[Merchant, II. vi. 43); go seek, etc.

Dr Abbott (sect. 349) says : ‘ We still

retain a dislike to use the formal to

after go and come, which may almost

be called auxiliaries, and we there¬

fore say, “ I will come and see

you.” ’

ACT SECOND.

Scene 1.

22.

2. Unstaid=:not staid, flighty. S. has also

the phrase : Unstaid and skittish.

See note on I. i. 121.

3. Nor . .. not. The Old English custom

in respect to negatives was to make

the one intensify or emphasise the

other. The Latin custom is that the

one annihilates the other, as in non-

nunquam, not never = sometimes.

The Latin custom did not come into

our language until after the middle

of the seventeenth century. The

English custom is seen in Matt. xxii.

46: * Ne nan ne dorste nan thing

acsian* (No one durst ask him any¬

thing) ; and in Chaucer’s Prologue,

70, 71, where he says of the Knight:

‘ He never yit no vileinye ne sayde,

In al his lyf, unto no maner wight.’

In each of these sentences there are

four negatives.

9. Listen’d. S. has also: A rrive the point

proposed; depart the chamber;

escaped the wreck; listen our pur¬

pose, etc. See Julius Ccesar, IV. i.

40 : ‘ Listen great things.’

10. Glose, flatter. Dr Schmidt explains it

as meaning to make mere words.

See Pericles, I. i. no: ‘He has

found the meaning, but I will glose

with him.’ It is also, once, found as

a noun in Love's Labour Lost, IV.

iii. 370: ‘Now to plain-dealing; lay

these gloses by.’ (From Gr. glossa,

a tongue ; and quite distinct from

gloss, shininess, which is connected

with the English glow.)

(yr>*V.

v VVJrV'VT' V . I* - a-

16.

26.

Undeaf. The only instance of the word.

See note on I. i. 121. S. uses deaf

as a verb twice.

Venom sound. See note on I. i. 172.

Fashions . . . Italy. In S.’s time, and

much earlier, Italian fashions were

much copied in England. See, for

the English habit of aping foreign

fashions, Merchant, I. ii. 61-63.

And in As You Like It, IV. i. 33,

Rosalind says : ‘ Farewell, Monsieur

Traveller: look you lisp and wear

strange suits, disable all the benefits

of your own country, be out of love

with your nativity.’

Still, always, ever. S. has the word

also as an adjective in the sense of

constant; in still practice. See also

Othello, I. iii. 147 : ‘ But still the

house-affairs would draw her hence.’

Tardy, always slow and behindhand.

S. has also : Tardy a?id remiss.

Apish. Cf. Richard III., I. iii. 49 :

‘Duck with French nods and apish

courtesy.’

Imitation, five syllables.

No respect = no thought.

III. i. 66:

Cf. Hamlet,

* There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.'

King John, III. i. 318: ‘ When such

profound respects do pull you on.’

Buzz'd, whispered. Cf. Henry VIII.,

II. i. 148 :

‘ Did you not of late days hear

A buzzing of a separation

Between the king and Katharine?’

NOTES TO RICHARD II.

109

men to sign and seal in blank, and

which they afterwards filled up with

what sums they pleased.

50. Subscribe them, put their names down.

52. Presently, immediately, at once. Cf.

Two Gentlemen, II. i. 30: ‘When

you fasted, it was presently after

dinner.' The procrastinating sense

of shortly, soon, is modern; though

S. sometimes uses it so.

54. Grievous sick. The dative oftheO.E.

adjective was used as an adverb—

as brighte =■ brightly; deepe, deeply.

This e was dropped; and then it

appeared as if any adjective could

be used as an adverb. This could

never have been the case with words

that came in—in the sixteenth cen-

53.

63.

tury—with the Revival of Learning;

but even these were so employed.

Thus S. has: Thou didst it excel¬

lent; equal ravenous ; noble spoken.

See Dr Abbott, sect. 1; and note on

I. iii. 3.

Ely House, the palace of the Bishop of

Ely, in Holborn (at the end of Oxford

Street, London), which has left its

name in Ely Place. See II. i. 216.

Go visit. S. has also: Come view

[Merchant, II. vi. 43); go seek, etc.

Dr Abbott (sect. 349) says : ‘ We still

retain a dislike to use the formal to

after go and come, which may almost

be called auxiliaries, and we there¬

fore say, “ I will come and see

you.” ’

ACT SECOND.

Scene 1.

22.

2. Unstaid=:not staid, flighty. S. has also

the phrase : Unstaid and skittish.

See note on I. i. 121.

3. Nor . .. not. The Old English custom

in respect to negatives was to make

the one intensify or emphasise the

other. The Latin custom is that the

one annihilates the other, as in non-

nunquam, not never = sometimes.

The Latin custom did not come into

our language until after the middle

of the seventeenth century. The

English custom is seen in Matt. xxii.

46: * Ne nan ne dorste nan thing

acsian* (No one durst ask him any¬

thing) ; and in Chaucer’s Prologue,

70, 71, where he says of the Knight:

‘ He never yit no vileinye ne sayde,

In al his lyf, unto no maner wight.’

In each of these sentences there are

four negatives.

9. Listen’d. S. has also: A rrive the point

proposed; depart the chamber;

escaped the wreck; listen our pur¬

pose, etc. See Julius Ccesar, IV. i.

40 : ‘ Listen great things.’

10. Glose, flatter. Dr Schmidt explains it

as meaning to make mere words.

See Pericles, I. i. no: ‘He has

found the meaning, but I will glose

with him.’ It is also, once, found as

a noun in Love's Labour Lost, IV.

iii. 370: ‘Now to plain-dealing; lay

these gloses by.’ (From Gr. glossa,

a tongue ; and quite distinct from

gloss, shininess, which is connected

with the English glow.)

(yr>*V.

v VVJrV'VT' V . I* - a-

16.

26.

Undeaf. The only instance of the word.

See note on I. i. 121. S. uses deaf

as a verb twice.

Venom sound. See note on I. i. 172.

Fashions . . . Italy. In S.’s time, and

much earlier, Italian fashions were

much copied in England. See, for

the English habit of aping foreign

fashions, Merchant, I. ii. 61-63.

And in As You Like It, IV. i. 33,

Rosalind says : ‘ Farewell, Monsieur

Traveller: look you lisp and wear

strange suits, disable all the benefits

of your own country, be out of love

with your nativity.’

Still, always, ever. S. has the word

also as an adjective in the sense of

constant; in still practice. See also

Othello, I. iii. 147 : ‘ But still the

house-affairs would draw her hence.’

Tardy, always slow and behindhand.

S. has also : Tardy a?id remiss.

Apish. Cf. Richard III., I. iii. 49 :

‘Duck with French nods and apish

courtesy.’

Imitation, five syllables.

No respect = no thought.

III. i. 66:

Cf. Hamlet,

* There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.'

King John, III. i. 318: ‘ When such

profound respects do pull you on.’

Buzz'd, whispered. Cf. Henry VIII.,

II. i. 148 :

‘ Did you not of late days hear

A buzzing of a separation

Between the king and Katharine?’

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

| Antiquarian books of Scotland > Languages & literature > Shakespeare's Richard II > (111) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/109386202 |

|---|

| Description | Thousands of printed books from the Antiquarian Books of Scotland collection which dates from 1641 to the 1980s. The collection consists of 14,800 books which were published in Scotland or have a Scottish connection, e.g. through the author, printer or owner. Subjects covered include sport, education, diseases, adventure, occupations, Jacobites, politics and religion. Among the 29 languages represented are English, Gaelic, Italian, French, Russian and Swedish. |

|---|