Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

26 THE LANGUAGE

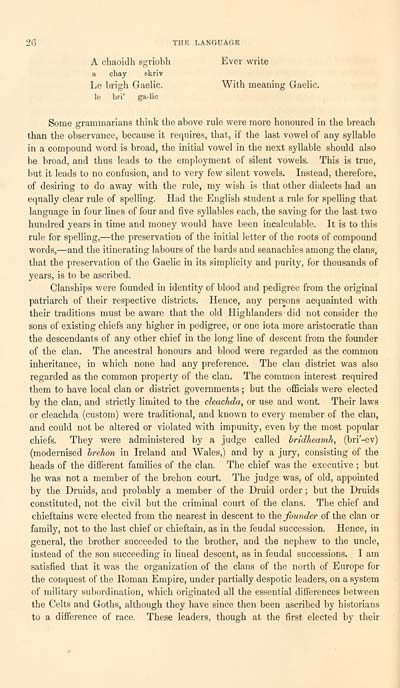

A chaoidh sgriobh Ever write

a, chay skriv

Le brigh Gaelic. With meaning Gaelic,

le bri' ga-lic

Some grammarians think the above rule were more honoured in the breach

than the observance, because it requires, that, if the last vowel of any syllable

in a compound word is broad, the initial vowel in the next syllable should also

be broad, and thus leads to the employment of silent vowels. This is true,

but it leads to no confusion, and to very few silent vowels. Instead, therefore,

of desiring to do away with the rule, my wish is that other dialects had an

equally clear rule of spelling. Had the English student a rule for spelling that

language in four lines of four and five syllables each, the saving for the last two

hundred years in time and money would have been incalculable. It is to this

rule for spelling, — the preservation of the initial letter of the roots of compound

words, — and the itinerating labours of the bards and seanachies among the clans,

that the preservation of the Gaelic in its simplicity and purity, for thousands of

years, is to be ascribed.

Clanships were founded in identity of blood and pedigree from the original

patriarch of their respective districts. Hence, any persons acquainted with

their traditions must be aware that the old Highlanders did not consider the

sons of existing chiefs any higher in pedigree, or one iota more aristocratic than

the descendants of any other chief in the long line of descent from the founder

of the clan. The ancestral honours and blood were regarded as the common

inheritance, in which none had any preference. The clan district was also

regarded as the common property of the clan. The common interest required

them to have local clan or district governments ; but the officials were elected

by the clan, and strictly limited to the cleachda, or use and wont. Their laws

or cleachda (custom) were traditional, and known to every member of the clan,

and could not be altered or violated with impunity, even by the most popular

chiefs. They were administered by a judge called hridheamh, (bri'-ev)

(modernised hrelion in Ireland and Wales,) and by a jury, consisting of the

heads of the diflerent families of the clan. The chief was the executive ; but

he was not a member of the brehon court. The judge was, of old, appointed

by the Druids, and probably a member of the Druid order ; but the Druids

constituted, not the civil but the criminal court of the clans. The chief and

chieftains were elected from the nearest in descent to the founder of the clan or

family, not to the last chief or chieftain, as in the feudal succession. Hence, in

general, the brother succeeded to the brother, and the nephew to the uncle,

instead of the son succeeding in lineal descent, as in feudal successions. I am

satisfied that it was the organization of the clans of the north of Europe for

the conquest of the Roman Empire, under partially despotic leaders, on a system

of military subordination, which originated all the essential diflerences between

the Celts and Goths, although they have since then been ascribed by historians

to a difi'erence of race. These leaders, though at the first elected by their

A chaoidh sgriobh Ever write

a, chay skriv

Le brigh Gaelic. With meaning Gaelic,

le bri' ga-lic

Some grammarians think the above rule were more honoured in the breach

than the observance, because it requires, that, if the last vowel of any syllable

in a compound word is broad, the initial vowel in the next syllable should also

be broad, and thus leads to the employment of silent vowels. This is true,

but it leads to no confusion, and to very few silent vowels. Instead, therefore,

of desiring to do away with the rule, my wish is that other dialects had an

equally clear rule of spelling. Had the English student a rule for spelling that

language in four lines of four and five syllables each, the saving for the last two

hundred years in time and money would have been incalculable. It is to this

rule for spelling, — the preservation of the initial letter of the roots of compound

words, — and the itinerating labours of the bards and seanachies among the clans,

that the preservation of the Gaelic in its simplicity and purity, for thousands of

years, is to be ascribed.

Clanships were founded in identity of blood and pedigree from the original

patriarch of their respective districts. Hence, any persons acquainted with

their traditions must be aware that the old Highlanders did not consider the

sons of existing chiefs any higher in pedigree, or one iota more aristocratic than

the descendants of any other chief in the long line of descent from the founder

of the clan. The ancestral honours and blood were regarded as the common

inheritance, in which none had any preference. The clan district was also

regarded as the common property of the clan. The common interest required

them to have local clan or district governments ; but the officials were elected

by the clan, and strictly limited to the cleachda, or use and wont. Their laws

or cleachda (custom) were traditional, and known to every member of the clan,

and could not be altered or violated with impunity, even by the most popular

chiefs. They were administered by a judge called hridheamh, (bri'-ev)

(modernised hrelion in Ireland and Wales,) and by a jury, consisting of the

heads of the diflerent families of the clan. The chief was the executive ; but

he was not a member of the brehon court. The judge was, of old, appointed

by the Druids, and probably a member of the Druid order ; but the Druids

constituted, not the civil but the criminal court of the clans. The chief and

chieftains were elected from the nearest in descent to the founder of the clan or

family, not to the last chief or chieftain, as in the feudal succession. Hence, in

general, the brother succeeded to the brother, and the nephew to the uncle,

instead of the son succeeding in lineal descent, as in feudal successions. I am

satisfied that it was the organization of the clans of the north of Europe for

the conquest of the Roman Empire, under partially despotic leaders, on a system

of military subordination, which originated all the essential diflerences between

the Celts and Goths, although they have since then been ascribed by historians

to a difi'erence of race. These leaders, though at the first elected by their

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Early Gaelic Book Collections > Blair Collection > Treatise on the language, poetry, and music of the Highland clans > (38) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/76236821 |

|---|

| Description | A selection of books from a collection of more than 500 titles, mostly on religious and literary topics. Also includes some material dealing with other Celtic languages and societies. Collection created towards the end of the 19th century by Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray. |

|---|

| Description | Selected items from five 'Special and Named Printed Collections'. Includes books in Gaelic and other Celtic languages, works about the Gaels, their languages, literature, culture and history. |

|---|