Volume 3 > Half-Volume 6

(247) Page 601 - Clark, Sir James

Download files

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

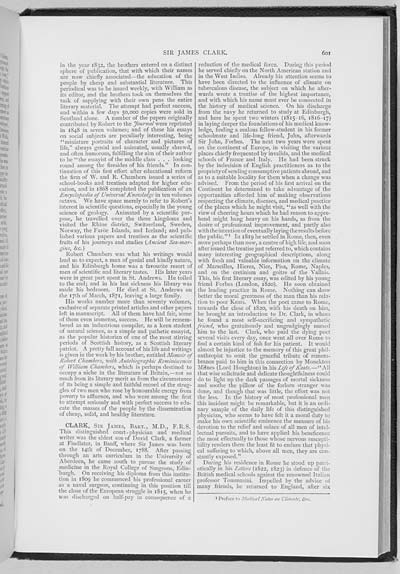

SIR JAMES CLARK. in the year 1832, the brothers entered on a distinct sphere of publication, that with which their names are now chiefly associated�the education of the people by cheap and substantial literature. This periodical was to be issued weekly, with William as its editor, and the brothers took on themselves the task of supplying with their own pens the entire literary material. The attempt had perfect success, and within a few days 50, 000 copies were sold in Scotland alone. A number of the papers originally contributed by Robert to the Journal were reprinted in 1848 in seven volumes; and of these his essays on social subjects are peculiarly interesting, being "miniature portraits of character and pictures of life, " always genial and animated, usually shrewd, and often humorous, fulfilling the aim of their author to be "the essayist of the middle class... looking round among the firesides of his friends. " In con- tinuation of this first effort after educational reform the firm of W. and R. Chambers issued a series of school-books and treatises adapted for higher edu- cation, and in 1868 completed the publication of an Encyclop�dia of Universal Knowledge in ten volumes octavo. We have space merely to refer to Robert's interest in scientific questions, especially in the young science of geology. Animated by a scientific pur- pose, he travelled over the three kingdoms and visited the Rhine district, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland; and pub- lished various papers and treatises as the scientific fruits of his journeys and studies (Ancient Sea-mar- gins, &c. ) Robert Chambers was what his writings would lead us to expect, a man of genial and kindly nature, and his Edinburgh home was a favourite resort of men of scientific and literary tastes. His later years were in great part spent in St. Andrews. He toiled to the end; and in his last sickness his library was made his bedroom. He died at St. Andrews on the 17th of March, 1871, leaving a large family. His works number more than seventy volumes, exclusive of separate printed articles and other papers left in manuscript. All of them have had fair, some of them even immense, success. He will be remem- bered as an industrious compiler, as a keen student of natural science, as a simple and pathetic essayist, as the popular historian of one of the most stirring periods of Scottish history, as a Scottish literary patriot. A pretty full account of his life and writings is given in the work by his brother, entitled Memoir of Robert Chambers, with Autobiographic Reminiscences of William Chambers, which is perhaps destined to occupy a niche in the literature of Britain, �not so much from its literary merit as from the circumstance of its being a simple and faithful record of the strug- gles of two men who rose by honourable energy from poverty to affluence, and who were among the first to attempt seriously and with perfect success to edu- cate the masses of the people by the dissemination of cheap, solid, and healthy literature. CLARK, SIR JAMES, BART., M. D., F. R. S. This distinguished court - physician and medical writer was the eldest son of David Clark, a farmer at Findlater, in Banff, where Sir James was born on the 14th of December, 1788. After passing through an arts curriculum in the University of Aberdeen, he came south to pursue the study of medicine in the Royal College of Surgeons, Edin- burgh. On receiving his diploma from this institu- tion in 1809 he commenced his professional career as a naval surgeon, continuing in this position till the close of the European struggle in 1815, when he was discharged on half-pay in consequence of a reduction of the medical force. During this period he served chiefly on the North American station and in the West Indies. Already his attention seems to have been directed to the influence of climate on tuberculous disease, the subject on which he after- wards wrote a treatise of the highest importance, and with which his name must ever be connected in the history of medical science. On his discharge from the navy he returned to study at Edinburgh, and here he spent two winters (1815-16, 1816-17) in laying deeper the foundations of his medical know- ledge, finding a zealous fellow-student in his former schoolmate and life-long friend, John, afterwards Sir John, Forbes. The next two years were spent on the continent of Europe, in visiting the various places chiefly frequented by invalids, and the medical schools of France and Italy. He had been struck by the indecision of English practitioners as to the propriety of sending consumptive patients abroad, and as to a suitable locality for them when a change was advised. From the period of his first arrival on the Continent he determined to take advantage of the opportunities afforded him of making observations respecting the climate, diseases, and medical practice of the places which he might visit, "as well with the view of cheering hours which he had reason to appre- hend might hang heavy on his hands, as from the desire of professional improvement, and partly also with the intention of eventually laying the results before the public. "1 In 1819 he settled in Rome, then, even more perhaps than now, a centre of high life, and soon after issued the treatise just referred to, which contains many interesting geographical descriptions, along with fresh and valuable information on the climate of Marseilles, Hieres, Nice, Pisa, Rome, Naples, and on the cretinism and goitre of the Vall�is. This, his first literary essay, was edited by his young friend Forbes (London, 1820). He soon obtained the leading practice in Rome. Nothing can show better the moral greatness of the man than his rela- tion to poor Keats. When the poet came to Rome, towards the close of 1820, with his death on him, he brought an introduction to Dr. Clark, in whom he found a most self-sacrificing and sympathetic friend, who gratuitously and ungrudgingly nursed him to the last. Clark, who paid the dying poet several visits every day, once went all over Rome to find a certain kind of fish for his patient. It would almost be injustice to the memory of this great phil- anthropist to omit the graceful tribute of remem- brance paid to him in this connection by Monckton Milnes (Lord Houghton) in his Life of Keats. �"All that wise solicitude and delicate thoughtfulness could do to light up the dark passages of mortal sickness and soothe the pillow of the forlorn stranger was done, and though that was little, the effort was not the less. In the history of most professional men this incident might be remarkable, but it is an ordi- nary sample of the daily life of this distinguished physician, who seems to have felt it a moral duty to make his own scientific eminence the measure of his devotion to the relief and solace of all men of intel- lectual pursuits, and to have applied his beneficence the most effectually to those whose nervous suscepti- bility renders them the least fit to endure that physi- cal suffering to which, above all men, they are con- stantly exposed. " During his residence in Rome he stood up patri- otically in his Lettere (1822, 1823) in defence of the British medical schools against the renowned Italian professor Tommasini. Impelled by the advice of many friends, he returned to England, after six 1 Preface to Medical Notes on Climate, &c. 6or

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen > Volume 3 > Half-Volume 6 > (247) Page 601 - Clark, Sir James |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/74514768 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

| Description | Volume III. Contains names alphabetically from Macadam to Young. |

|---|