Volume 3 > Half-Volume 6

(226) Page 580

Download files

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

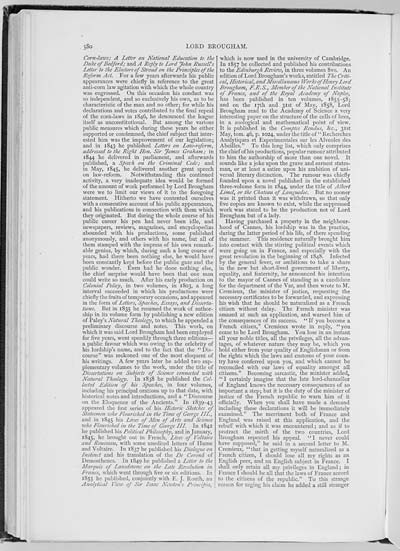

580 Corn-laws; A Letter on National Education to the Duke of Bedford; and A Reply to Lord John Russell's Letter to the Electors of Stroud on the Principles of the Reform Act. For a few years afterwards his public appearances were chiefly in reference to the great anti-corn law agitation with which the whole country was engrossed. On this occasion his conduct was so independent, and so exclusively his own, as to be characteristic of the man and no other; for while his declarations and votes contributed to the final repeal of the corn-laws in 1846, he denounced the league itself as unconstitutional. But among the various public measures which during these years he either supported or condemned, the chief subject that inter- ested him was the improvement of our legislation; and in 1843 he published Letters on Law-reform, addressed to the Right Hon. Sir James Graham; in 1844 he delivered in parliament, and afterwards published, a Speech on the Criminal Code; and in May, 1845, he delivered another great speech on law-reform. Notwithstanding this continued activity, a very inadequate idea would be formed of the amount of work performed by Lord Brougham were we to limit our views of it to the foregoing statement. Hitherto we have contented ourselves with a consecutive account of his public appearances, and his publications in connection with them which they originated. But during the whole course of his public career his pen had never been idle, and newspapers, reviews, magazines, and encyclopedias abounded with his productions, some published anonymously, and others with his name, but all of them stamped with the impress of his own remark- able genius, by which, during such a long course of years, had there been nothing else, he would have been constantly kept before the public gaze and the public wonder. Even had he done nothing else, the chief surprise would have been that one man could write so much. After his early production on Colonial Policy, in two volumes, in 1803, a long interval succeeded in which his productions were chiefly the fruits of temporary occasions, and appeared in the form of Letters, Speeches, Essays, and Disserta- tions. But in 1835 he resumed the work of author- ship in its volume form by publishing a new edition of Paley's Natural Theology, to which he appended a preliminary discourse and notes. This work, on which it was said Lord Brougham had been employed for five years, went speedily through three editions� a public favour which was owing to the celebrity of his lordship's name, and to the fact that the "Dis- course" was reckoned one of the most eloquent of his writings. A few years later he added two sup- plementary volumes to the work, under the title of Dissertations on Subjects of Science connected -with Natural Theology. In 1838 he published the Col- lected Edition of his Speeches, in four volumes, including his principal orations up to that date, with historical notes and introductions, and a "Discourse on the Eloquence of the Ancients." In 1839-43 appeared the first series of his Historic Sketches of Statesmen who Flourished in the Time of George III., and in 1845 his Lives of Men of Arts and Science who Flourished in the Time of George III. In 1842 he published his Political Philosophy, and in January, 1845, he brought out in French, Lives of Voltaire and Rousseau, with some unedited letters of Hume and Voltaire. In 1837 he published his Dialogue on Instinct and his translation of the De Coron� of Demosthenes. In 1849 he published a Letter to the Marquis of Lansdowne on the Late Revolution in France, which went through five or six editions. In 1855 he published, conjointly with E. J. Routh, an Analytical View of Sir Isaac Newton's Principia, which is now used in the university of Cambridge. In 1857 he collected and published his contributions to the Edinburgh Review, in three volumes 8vo. An edition of Lord Brougham's works, entitled The Criti- cal, Historical, and Miscellaneous Works of Henry Lord Brougham, F.R.S., Member of the National Institute of France, and of the Royal Academy of Naples, has been published in ten volumes, 1855-58;. and on the I7th and 31st of May, 1858, Lord Brougham read to the Academy of Science a very interesting paper on the structure of the cells of bees,, in a zoological and mathematical point of view.. It is published in the Comptes Rendus, &c., 31st May, torn. 46, p. 1024, under the title of '' Recherches Analytiques et Experimentales sur les Alveoles des Abeilles. " To this long list, which only comprises the chief of his productions, popular rumour attributed to him the authorship of more than one novel. It sounds like a joke upon the grave and earnest states- man, or at least a satire upon his ambition of uni- versal literary distinction. The rumour was chiefly founded upon a novel published in the established three-volume form in 1844, under the title of Albert Limel, or the Chateau of Languedoc. But no sooner was it printed than it was withdrawn, so that only five copies are known to exist, while the suppressed work was stated to be the production not of Lord Brougham but of a lady. Having purchased a property in the neighbour- hood of Cannes, his lordship was in the practice, during the latter period of his life, of there spending the summer. This residence naturally brought him into contact with the stirring political events which were going on in France, and especially with the great revolution in the beginning of 1848. Infected by the general fever, or ambitious to take a share in the new but short-lived government of liberty, equality, and fraternity, he announced his intention to the mayor of Cannes of standing as a candidate for the department of the Var, and then wrote to M. Cremieux, the minister of justice, requesting the necessary certificates to be forwarded, and expressing his wish that he should be naturalized as a French citizen without delay. The French minister was amazed at such an application, and warned him of the consequences of its success. "If you become a French citizen," Cremieux wrote in reply, "you cease to be Lord Brougham. You lose in an instant all your noble titles, all the privileges, all the advan- tages, of whatever nature they may be, which you hold either from your quality of Englishman or from the rights which the laws and customs of your coun- try have conferred upon you, and which cannot be reconciled with our laws of equality amongst all citizens." Becoming sarcastic, the minister added, "I certainly imagine that the late lord-chancellor of England knows the necessary consequences of so important a step; but it is the duty of the minister of justice of the French republic to warn him of it officially. When you shall have made a demand including these declarations it will be immediately examined." The merriment both of France and England was raised at this application, and the rebuff with which it was encountered; and as if to protract the mirth of the two countries, Lord Brougham repeated his appeal. "I never could have supposed," he said in a second letter to M. Cremieux, "that in getting myself naturalized as a French citizen, I should lose all my rights as an English peer, and an English subject in France. I shall only retain all my privileges in England; in France I should be all that the laws of France accord to the citizens of the republic." To this strange reason for urging his claim he added a still stranger

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen > Volume 3 > Half-Volume 6 > (226) Page 580 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/74514726 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

| Description | Volume III. Contains names alphabetically from Macadam to Young. |

|---|